The Mary Rose and the birth of the Royal Navy

Construction and War: 1510 – 1520

Henry VIII was an enthusiastic shipbuilder, whose pride in his “Army by Sea” would see his fleet grow from 5 at the start of his reign to 58 by the time of his death in 1547. While he may have had many ships, it is the Mary Rose that is remembered as his favourite. Notably, the life of the Mary Rose coincides almost exactly with the reign of Henry VIII.

Before the development of a standing Navy, English kings relied upon requisitioning merchant vessels in times of need. This was certainly cheaper than building, maintaining and manning ships in times of peace, but it was inefficient and difficult to mobilize. With the threat of Scotland to the north and France to the south, Henry VIII began to build his Navy as soon as he came to the throne.

The Mary Rose and the Peter Pomegranate

The earliest reference to the Mary Rose is 29th January 1510, in a letter ordering the construction of “two new ships”. These ships were to be the Mary Rose and her 'sister' ship, the Peter Pomegranate. The ships were built in Portsmouth, making the sinking of the Mary Rose in the Solent and her eventual resting place in Portsmouth’s Mary Rose Museum all the more poignant.

The Peter Pomegranate

'Sister' ship of the Mary Rose

When the Mary Rose was built in 1510, she wasn't built on her own. A second, smaller ship was commissioned at the same time...

“Right worshipful sir, I heartily recommend me unto you, [...] furthermore desiring your mastership that for the indenture of parchment that I delivered unto you there may be made another new, extending to the whole sum of money as it specifieth of bearing the date and time according; but whereas it specifieth several sums of money, so much [...] to the Mary Rose and Peter Pomegranate [...]

Written at Woolwich, the 9th day of the month of June

By your own Robert Brigandine, Clerk of Ships”

Built in 1510 in Portsmouth, The Peter Pomegranate was a 300 ton carrack, enlarged to 600 tonnes in 1536, presumably at the same time as her sister's refit.

Her name probably comes from St Peter and the Pomegranate, which as well as having symbolic links to St Peter, much as the Rose had links with the Virgin Mary, was also the emblem of the House of Aragon, the king’s in-laws when the ship was built. Of course, when Henry VIII divorced Catherine of Aragon, he changed the name of the ship to just “Peter”

The Peter Pomegranate fought in the War of the Holy League alongside the Mary Rose, with Sir Wistan Browne as her captain.

We’re not sure of the fate of the Peter Pomegranate; other than taking part in action against the Scots in 1547, her last appearance in records is just a mention in 1558.

A list of her armaments in 1545 can be found in the Anthony Roll, which also features the Mary Rose and the rest of the Kings fleet.

The first account that names the Mary Rose is a letter from June 1511. It is often claimed that the ship was named after Henry’s sister, Mary Tudor but no evidence supports this. Instead, it was the fashion to name ships for saints and the pairing of the Mary with the Peter supports this. The badges of the ships – the Rose and the Pomegranate – celebrate the royal couple; the rose being the symbol of the king, and the pomegranate being that of his first wife, Katherine of Aragon. Neatly, the Virgin Mary was known at the time as the ‘Mystic Rose’; the name of the Mary Rose therefore signifies not only the power of the Tudor dynasty, but also that of the Virgin Mary.

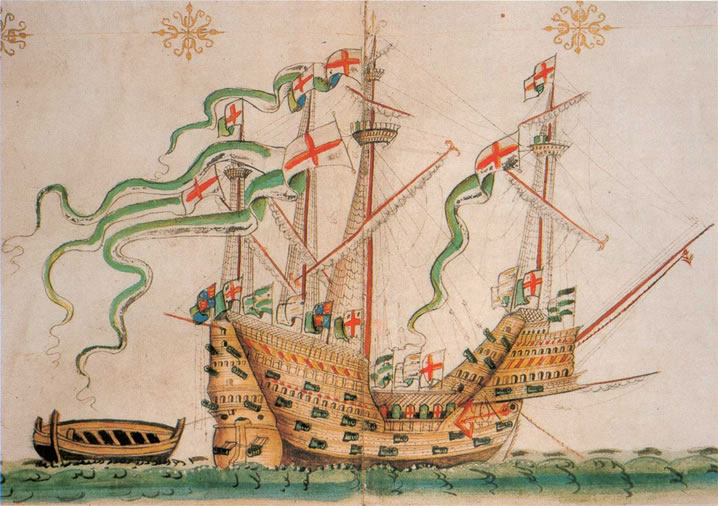

The Mary Rose was larger than her sister ship - 600 tons to the Peter Pomegranate’s 450 - but this was not the only difference between the ships. While both were carracks designed for war, the Peter Pomegranate was not built to carry heavy guns. The Mary Rose, on the other hand, carried six or eight large guns from the beginning of her career. This required a new design feature: gun ports. The Mary Rose was therefore of a state-of-the-art design. It has been suggested that Henry himself insisted on the design, which would add to the reasons why he was so proud of the Mary Rose.

Six months after the launch of the Mary Rose, Henry VIII was at war with France; the nineteen year old king wanted to show his mettle against the might of France. Against the advice of his father’s old advisers, Henry VIII declared war in 1512.

The Battle of St Mathieu

While the Mary Rose was not the largest of Henry’s ships – the 1000 ton Regent held that position – it was the Mary Rose that the Admiral of the Fleet, Edward Howard, picked as his flagship. This was to be a matter of significance in the Battle of St Mathieu on the 10th August 1512.

In the weeks leading up to the battle, Howard led successful raids along the coast of Brittany, capturing 40 French ships and sacking French towns. He returned to Portsmouth in late July in order to resupply where he was visited by the king. On the 6th August, Howard received word that the French navy had mobilized and he left Portsmouth to return to Brittany.

The French did not expect the English to arrive for several more days and were celebrating the Feast of St Lawrence when the English fleet arrived. Many French officers were celebrating the saint’s day on land, while local dignitaries and their families were feasting aboard the fleet. Upon seeing the English fleet, the large majority of the French ships fled, their retreat guarded by the French flagship, the Grand Louise, and the Cordelière.

The Mary Rose drew first blood; she shot out the mainmasts of the Grand Louise, killing 300 men and taking the ship out of commission. This short engagement marks the first instance of ships fitted with gunports engaging each other at range without an attempt of boarding, a watershed moment in naval history.

Despite this historic action, the most dramatic action of the day did not include the Mary Rose. While the Mary Rose was engaged with the Grand Louise, the 1000 ton English Regent grappled with the Cordelière. As with many of the French ships, the Cordelière was hosting families as the English fleet arrived and her captain, Hervé de Porzmoguer, made the hard decision to fight with civilians on board. As the ships grappled with one another, there was a suddenexplosion aboard the Cordelière. The flames spread to the Regent and both ships went down. Over 1500 people died from the two ships, including women and children aboard the Cordelière.

In September 1512, the campaigning season came to an end. The Mary Rose returned to England and moored in the Thames throughout the winter.

She did not sit idle for long, however. In March 1513, Admiral Howard organised a race of the fleet along the coast of Kent to “test their abilities”. The Mary Rose finished half a mile ahead of the Sovereign, the next fastest ship, with Howard declaring that the Mary Rose“is the noblest ship of sail of any great ship, at this hour, that I know in Christendom”.

The death of Admiral Sir Edward Howard

In April 1513, the English fleet, including the Mary Rose, returned to harass the French coast at Brest. The French retreated, taking a defensive position against the English. Itching for a fight, Howard entered several skirmishes, anxious to achieve some sort of victory.

On the 22nd April 1513, the French attacked the English fleet, sinking one ship and badly damaging another. Howard retaliated, leading a force to board the galley of the veteran French commander Prégent de Bidoux. Howard was last seen shouting “Come aboard again! Come aboard again!” to his men before he was cut down.

Demoralised after the death of the Admiral, the English fleet fled back to Plymouth. Lord Thomas Howard, older brother of Sir Edward, was appointed Admiral of the Fleet and also choose the Mary Rose as his flagship. Incidentally, Lord Thomas Howard would later become the third Duke of Norfolk, and was uncle to both Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard.

The Battle of Flodden

The next significant moment in the Mary Rose’s career was her involvement in the preparations for the Battle of Flodden Field. While Henry VIII was campaigning in France, King James IV of Scotland made the most of the opportunity and led an invasion of England.

The queen regent, however, successfully organised the defence of the north with the assistance of the Earl of Surrey (the father of Lord Thomas Howard). The Mary Rose was part of this victory as a troop transport ship. King James IV of Scotland died at the Battle of Flodden Field on 9th September 1513.

By 1514, enthusiasm for the war was diminishing on both sides.

Skirmishes continued until a peace was signed, with the Mary Rose involved in the final fighting of the war on the 14th June 1514. On the 9th October 1514, a peace between England and France was officially sealed with the marriage of Henry’s sister, Princess Mary Tudor, with King Louis XII of France.

In July 1514, the Mary Rose, along with most ships in the king’s navy, was decommissioned in Deptford. This saw the dismantling of the masts and rigging, the removal of anchors, pulleys and other such equipment, as well as the removal of the armaments of the ship.

The Mary Rose briefly returned to service in June 1520 as Henry mobilized all of his most prestigious ships to escort him to France for the meeting of the Field of the Cloth of Gold. This meeting between Henry and Francis I of France was a glamorous display of the wealth and grandeur of the two countries, as the two rival kings attempted to find solutions to their differences and prevent future wars. Everything about the meeting was designed to awe the opposition; as such the inclusion of the Mary Rose in the king’s escort was inevitable.

Favourite of the Fleet: 1520 – 1530

In 1522, just two years after the Field of the Cloth of Gold, England and France were at war once again, with Henry siding with Charles V of Spain, the nephew of Queen Katherine. In May 1522, Charles arrived in England. At 2pm on the 30th May 1522, the two kings boarded and inspected the Henry Grace a Dieu and the Mary Rose; Henry was showing off his favourite ships.

Shortly afterwards, the fleet set off from Southampton. Lord Thomas Howard, now the Earl of Surrey, decided to use the Mary Rose as his flagship; the superior sailing of the Mary Rose trumped the size of the Great Harry. Surrey successfully attacked the Breton port of Morlaix on 1st July 1522 but the supplies that he requested in order to take Brest never arrived. He had no choice but to return to Portsmouth. The Admiral was redeployed and given command of a land force at Calais at this point; the Vice-Admiral, Sir William Fitzwilliam, also chose the Mary Rose to be his flagship. The Mary Rose had now been the preferred ship of Sir Edward Howard, Lord Thomas Howard and Sir William Fitzwilliam.

The second war with France was mostly a collection of skirmishes, with very little actually happening until 1525 and the Battle of Pavia, which ended the war. The English, however, had nothing to do with Pavia, which saw King Francis captured by Spanish forces. The fleet does not seem to have been mobilised at all throughout 1525 and the Mary Rose was moved to Deptford that summer to be recaulked.

The Refit: 1530 – 1540

In Ordinary

The Mary Rose was largely inactive for the first five years of the 1530s.

From January 1536 to March 1537, the Mary Rose could be seen in the Thames without her masts. As tensions mounted in Europe as a result of Henry’s break from the Church of Rome, Henry began reinforcing his warships and the Mary Rose underwent a refit. Extra gunports were added and the sides of the ship were strengthened in order to accommodate the extra weight.

Unfortunately, the new alterations to the Mary Rose may have cost her her impressive sailing. In April 1537, Vice-Admiral John Dudley reportedly that some of the ships were “unweatherly” and that “the ship that Mr Carew is in” was particularly bad. While it’s not clear which ship “Mr Carew” was on, George Carew was the captain of the Mary Rose when she sank eight years later; it is not impossible that the problematic ship was the Mary Rose.

In 1539, Henry mobilized the fleet once more, in fear of a joint invasion from France and Spain. Henry had been excommunicated by the Pope for declaring himself Head of the Church of England and he feared the Catholic powers of Europe would attack. In the summer of 1539, the Mary Rose was anchored at Deptford, ready to defend the Thames.

The Last Years: 1540-45

Henry’s fears of a combined Franco-Spanish invasion came to nothing as the treaty between Francis and Charles fell apart by 1539. However, Henry’s fleet remained prepared throughout the campaigning months of 1539-1542.

In June 1542, Henry entered an alliance with Charles of Spain against Francis, thus beginning Henry’s last war with France. The reasons for Henry entering this war are unclear, although it is worth noting that his fifth wife, Catherine Howard, had been found guilty of adultery and executed just four months previously; perhaps Henry was desperate to prove his power and masculinity in the face of this humiliation.

It is not known whether or not the Mary Rose was part of the fleet that took Henry himself to Calais in 1544, although it is likely, since most of the fleet was involved. In September 1544, Henry captured the French town of Boulogne. However, his alliance with Charles of Spain fell apart and England was left isolated against France.

The French retaliation for Boulogne was to prove fatal for the Mary Rose.

July 1545: The Battle of the Solent and the sinking of the Mary Rose

Claude d’Annebault, the French Admiral, gathered over 200 ships in the estuary of the River Seine. This fleet was significantly larger than the Spanish Armada nearly 50 years later, which totalled 130 ships. Against this number, the English amassed around 80 ships.

John Dudley, Viscount Lisle, was Lord Admiral of the Fleet and he did not intend to sit wait for the French attack. Lisle sent fireships in amongst the anchored French fleet at Le Havre to burn the French ships; the French flagship, the 100-gun Philippe, burned. Ominously for the French, the next ship chosen to hoist the Admiral’s flag then ran aground and had to be abandoned.

On the 12th July 1545, the French set sail, reaching the Sussex coast on the 18th. After an insignificant raid in Sussex, the French fleet entered the Solent on the 19th July.

The night before (18th July 1545), King Henry VIII dined aboard his flagship, the Great Harry, with Viscount Lisle and Sir George Carew, where Carew was appointed Vice-Admiral of the Fleet and given command of the Mary Rose.

The loss of the Mary Rose

When the French fleet arrived, Henry watched from Southsea Castle. The lack of wind gave the French the advantage, the oared French galleys able to advance while the large sailing ships were immobile. Towards the afternoon, however, the wind rose and Lisle led out his large ships, including the Mary Rose.

The Mary Rose fired from her starboard side, then came about to fire from the port side. As she turned, she listed to one side, her starboard side low in the water. The Spanish Ambassador Francois van der Delft, an eyewitness to the battle, wrote that the ship “heeled over with the wind”. The starboard gunports were, crucially, left open, and, with the final nudge from the wind, they fatally dipped below the waterline. The water flooded in and the ship went down in a matter of minutes. Of the nearly 500 men on board, no more than 35 survived.

Despite the tragedy of losing the Mary Rose, she was the only loss of the battle. The two fleets sat in a deadlock in the Solent, a situation that favoured the English, who only needed to hold the port and who had supplies and reinforcements. On the 23rd July 1545, d’Annebault made the decision to retreat

What happened next?

Historical | 09 Jan, 2014 | Museum Blogger

Why did an invasion fleet, nearly twice the size of the later Spanish Armada, just pack up and leave?

The Battle of the Solent, on 19th July 1545, is one of those events in history that had the potential to be very important, but is pretty much unknown. Indeed, many people who live near the Solent probably would never have heard of this battle on their doorstep if it weren't for the loss of the Mary Rose, and her recovery in 1982.

Most accounts of the Battle of the Solent (which appears to be a name attributed to this conflict sometime later, as no contemporary accounts use this nomenclature) only cover the period leading up to the sinking of the Mary Rose, as if that was the defining point of the battle. But what happened next? Why did an invasion fleet, nearly twice the size of the later Spanish Armada, just pack up and leave?