Shipwreck narratives of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century: indicators of culture and identity(I)

MARGARETTE LINCOLN

The shipwreck is a recurrent theme in religious and secular literature and in the visual arts. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the most popular focus of interest in shipwrecks was the 'eyewitness account'. There are many examples of such narratives, since during this period shipwreck was an everyday occurrence. Often these accounts were published in inexpensive editions soon after a ship was lost. Some were published as cheap repository tracts, or included in works for children. Some were aimed at travellers who, in venturing abroad, would have to risk danger and death at sea. Some included the adventures of survivors in foreign lands. In the case of a few, well-publicised disasters they appear to have formed part of the process of public mourning. In other cases the survivors seem compelled to complete the story that began when the ship left port.

Shipwreck narratives record moments of crisis in which social conventions are tested in isolation from the conditions that normally support them. They are moments in which assumptions about divine Providence, about national character, about gender roles, about civilised behaviour, are placed at risk or thrown into unusually sharp definition. For this reason the narratives bring into focus many aspects of contemporary British culture. lt is hardly surprising that novelists and poets drew heavily on published accounts of disasters at sea. There is some evidence that painters too made use often in a search for 'authenticity'. Although the iconology of shipwrecks has been studied (the most recent account appearing fourteen years ago), there has never been a study of the shipwreck narrative. This paper offers a preliminary account of the cultural significance of this popular and influential form. lt examines the conditions within which the shipwreck narrative appeared, explores the concepts that circulated within the genre, and considers its interaction with the arts.

![]()

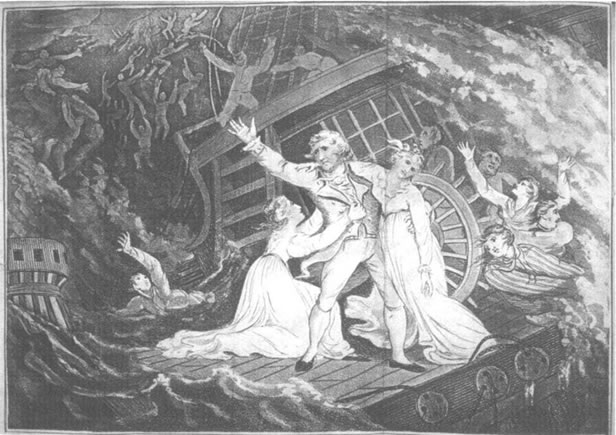

Several of these themes are focused in an illustration which accompanies an account of the loss of the Halsewell East Indiaman, which foundered in r 786. Captain Pierce of the Halsewell had his two daughters on board and hoped to save them. Several men managed to scramble to the rocks and safety, but the women passively awaited their fate in the ship's round house. The ship broke up and they were drowned. The illustration reinforces the captain's dilemma which is placed at the heart of the narrative. He is shown on deck, a daughter clinging helplessly, though gracefully, on either side. The daughters' flowing dresses make them seem incapable of movement. Certainly their presence stops the captain from attempting to save his own life, though he is depicted as both strong and energetic. His resolute stance implies determination to do his duty by staying with his daughters, though the out flung arm suggests frustration that he can do nothing to save them. The girls themselves seem distressed but not panic-stricken as others of lesser rank appear to be. Their white dresses suggest purity; they occupy the only dry spot on deck as towering waves threaten to engulf them. This representation of the disaster reinforces contemporary class and gender boundaries. Extreme situations crystallise in dramatic form social and moral tensions and it is this aspect of shipwreck narratives that merits close examination.

In the eighteenth century, there was a burgeoning travel literature. Some accounts purported to be factual, others offered sensation and novelty. In utopian form, travel literature included fantastic voyages to the moon and Crusoe-like shipwrecks in imaginary lands. This great era of travel writing coincided with the rise of the novel, and travelogues sometimes display a blend of factuality and creativity more typically thought of as characterising 'realistic' fiction. Shipwreck narratives can be regarded as a sub-genre of travel writing although Defoe's Robinson Crusoe demonstrates that shipwreck can sustain complex fictional treatment. The familiarity of shipwreck as a topos meant that it could also be used in almost cursory fashion to effect sudden reversals in narrative, for example in picaresque fiction and in Candide where Voltaire's shipwreck episode helps to satirise the belief that all is for the best in the best of all possible worlds. The disaster takes place within sight of the port of Lisbon, implicitly questioning Providence (though sailing ships were often wrecked near coasts), and one of the three survivors is a brute of a sailor who has just drowned a virtuous Anabaptist.

The interpretation of shipwreck narratives designed for popular consumption needs to be informed by our awareness of these more literary or mythic uses of shipwreck. Inevitably shipwreck narratives influenced the representation of shipwrecks in the literature and visual arts of the period. Novelists and poets drew heavily on 'true' accounts of disasters at sea and there are parallels with their use of the Newgate Ordinary's Accounts. In turn, the influence on shipwreck narratives of Defoe's Robinson Crusoe, continually reprinted, is inescapable. Crusoe constituted a blueprint by which subsequent tales of wreck and survival might be measured. Later the Romantics were drawn to scenes of shipwreck, which allowed them to represent extremes of human experience. Byron's debt to shipwreck narratives is well documented. Recently critics have noted that the sea and intimations of shipwreck are persistent motifs in women's poetry of the period. Women, of course, had fewer opportunities to go to sea. Their poems feature isolated women gazing out to sea from the shore, awaiting the return of loved ones and repressing fears for their safety. Or the sea's different moods are used to reflect their inner turmoil. Charlotte Smith, who wrote several poems featuring the sea, also wrote an account of the wreck of the Catherine, published by subscription for the assistance of a female survivor and her child. This suggests that the iconography of the sea was powerful chiefly because the actual power of the sea was so frequently impressed upon those living at the time.

Because shipwreck was an everyday occurrence (one source claims that in the 1750s around 4200 Britons a year perished at sea), tales of shipwreck had popular appeal. Many narratives were embellished to make them more sensational. Authenticity had a market value; most authors of shipwreck narratives write in the first person and are at pains to assure readers that their stories are records of fact. This is signalled at the outset in the title: narratives are 'surprizing yet real and true', 'written from authentic documents', taken 'from the journal alone of the surviving officers' or 'faithfully abstracted from letters'. Shipwreck narratives were to some extent shaped by the market, and the religious and economic need to portray disasters and near disasters in a positive light. Most have a strong emotional appeal. Whenever circumstances permit, for example, the narratives seek to elicit pathos through descriptions of terrified and bewildered children who, like their mothers, were Jess likely to survive. Yet shipwreck accounts - however sensational - could be used to promote religious and moral lessons. (Conversely, moral lessons could also be used to justify publishing sensational accounts, producing an interplay of different discourses.) Some survivors call witness to merciful providence - without dwelling overmuch on those who unfortunately perished. Others demonstrate how perseverance is rewarded when individuals who persist in the fight for survival are rescued against the odds. A frequently expressed motive for publication (perhaps disingenuous) is to offer reader’s practical hints should they ever find themselves in similar desperate circumstances. And there is some evidence that prospective travellers did scan shipwreck narratives in the hope of finding practical guidance.

For all these reasons, when news of an important wreck hit the streets, there was a ready market for cheap pamphlets giving an 'accurate' account of the disaster. Often these pamphlets or chapbooks were simply re-written newspaper reports, though the author may have been able to interview survivors. Collections of shipwreck narratives were compiled from such chapbooks, and from news papers and magazines. If a book had been devoted to a single catastrophe, it might be summarised. The earliest collection of narratives of shipwrecks is thought to be Mr James Janeway's legacy ta his friends, containing twenty-seven famous instances of God's Providence in and about sea-dangers and deliverances (London 1675). But the anthology which provided the source for later collections is Archibald Duncan's The Mariner's chronicle. Between 1804 and 181 o this work saw three editions in London and two in Philadelphia. Later compilers copied Duncan, or each other, and included accounts of other disasters as they occurred.

The most notable publisher of shipwreck narratives was Thomas Tegg of 111 Cheapside, London. Tegg was a famous populariser who dealt in remainders and made a fortune with his cheap reprints and abridgements of popular works. From about 1805 to 1810 he produced a series of 28-page pamphlets - some 30 titles in all - each devoted to one shipwreck or summarising two or three maritime disasters. The pamphlets were put together by anonymous hack writers and are undated, though each has a folding aquatint as frontispiece which is dated.

These tales sold for 6d and were extremely good value in an age when some uncoloured prints cost that much alone. Clearly there was a market for such material among wealthier classes, too. In 1809, Tegg produced The Mariners' marvellous magazine, or wonders of the ocean containing the most remarkable adventures and relations of mariners in various parts of the globe. One edition, grandly advertised as being in four volumes, sold simultaneously in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dublin. Yet The Mariners' marvellous magazine is just a compilation of Tegg's popular 28-page pamphlets; the pages have not even been re-numbered consecutively.

I

Sea travel had a specific religious frame of reference which meant that embarking on any voyage was potentially an act of symbolic significance. The sea had made possible the journeys of St Paul and (despite his shipwreck) had facilitated the spread of the Christian faith. It was also regarded with fear and suspicion. The early Christian fathers encouraged people to think of life as a journey or a voyage fraught with perils. The unstable sea came to represent the fragility of life and served to remind people why faith in God was necessary. In this context, the Church was symbolised as a ship. Thus the title page of The Causes of the decay of Christian piety (London 1668), lamenting the apparent decline of religion in Restoration England, shows a ship consumed by flames. Storm and shipwreck were often interpreted as a divine punishment - the story of the Flood showed that the ocean might be an instrument of punishment. Or the sea might symbolise Purgatory since storms induced penitence. In short, shipwrecks could be interpreted as a punishment, a test, or a means of spiritual education. Obviously, lessons could be learnt by survivors, and also by readers contemplating the misfortunes of others.

In the later eighteenth century, the religious symbolism of shipwreck accounts became less overt but never entirely disappeared. The religious significance accorded to particular shipwrecks varies with the date of publication and the disposition of the author. The declared aim of many named authors is to strengthen the faith of readers, whether the particular disaster is viewed as an example of divine retribution or mercy. Others seem merely to pay lip service to recognised forms of religious interpretation.

As shipwreck narratives lent themselves to religious interpretation, they were published in abridged form as cheap repository tracts that could be hawked around the country, and included in works for children. In 1799 a British society dedicated to 'the suppression of vice and immorality' published The Entertaining, moral and religious repository 'for the amusement and instruction of the youth of both sexes'. It included a comforting story called 'Wonderful escape from shipwreck'. Another publication, The History of the holy Jesus [...] a pleasant and profitable companion for children, reprinted fifteen times between 1764 and 1774, was always issued with verses on 'St Paul's shipwreck'. Disasters at sea continue to be used to entertain and instruct younger readers. The Whitbread Award for the best children's novel bas recently been awarded to Michael Morpurgo for his book The Wreck of the Zanzibar, set in the storm-beaten Scilly Isles. The formula is an enduring one.

In the nineteenth century, there were many compilations of shipwreck narratives. Some, apparently aimed at seamen, include descriptions of various expedients for saving lives using lifeboats and life preservers. Several compilations were produced by religious societies: the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK) and the Religious Tract Society. These teach that the best chance of safety is secured by prompt obedience to captain's orders and attention to duty in moments of crisis. On the other hand, they also stress that he who trusts in God with a clear conscience is most able to cope with danger, 'for while his sense of duty will urge him to do all that can be done for the general safety, his faith and confidence in a Father's love and care will enable him to accept the result without a murmur'. The use to which such publications were put is suggested by the inscription on one SPCK volume: 'British Sailors Reading Room Dieppe from the Rt Revd Bishop Turner, 1862. Certainly, most of the stories in this later volume have an ideological slant that reinforces training and discipline at sea, though the result is sometimes an uneasy tension with the book's religious purpose. The conclusion to the account of the loss of the Proserpine is typical of this dual focus. Though she was trapped in ice off Newark Island in the winter of 1799, all but fourteen of her crew reached safety. We are told that 'they displayed unflinching courage and discipline in the midst of anxiety and danger, and hardships rarely paralleled; and to their own fortitude and perseverance in the hour of peril they owed, under Providence, their final deliverance'.

II

Shipwreck narratives also reveal attitudes to national identity 1816. The French frigate Medusa, taking out a viceroy to one of the French colonies on the coast of Africa, struck a sand bank some 40 miles from the shore. Her captain, who had already shown great incompetence, was among the first to scramble into a boat. The ship's boats could not carry all those on board and, in any case, pushed off from the sides of the frigate before they were full. A raft was hastily built for the remaining150 passengers and taken in tow by the boats. There was little food on the raft and not a single naval officer to take charge. In a short time, though the sea was calm, the men in the boats cast off the tow lines and abandoned their countrymen to their fate. In the terrible confusion that followed, the raft became the site of murder and cannibalism. After seventeen days, only fifteen survived to be picked up by a brig, sent out by the ship's crew who had meanwhile reached safety. An account of the disaster, by A. Corréard and J.B. H. Savigny, was published in a London edition in 1818. Théodore Géricault's famous painting, displayed in the Paris Salon in 1819 and in London the following year, served to fix the horror of the scene in the popular mind. The scandal was embarrassing for the new royalist regime that had succeeded Napoleon in France, and the wreck quickly assumed political significance - so much so that plays representing the disaster could not be performed in France until after a change in government in 1839. Even then details of the event were concealed. Charles Desnoyer's Un naufrage de la Méduse, drame en cinq actes imitates Géricault's picture not the event itself, treating the wreck scene as a tableau.

It was commonly accepted that the manner in which British crews coped with disaster reflected on the nation and its aspirations. So, for example, when details of the infamous Medusa wreck were made public in the year after Waterloo, British authors felt sure that nothing so heinous could have taken place on a British ship. British writers commonly contrasted the wreck of the Medusa with that of the British frigate Alceste, which happened about the same time in 1817. Narratives of the event help to show how the British national character was constructed partly by comparison with the French. The Alceste struck a reef in the Straits of Gaspar. The crew occupied a nearby island where they were attacked repeatedly by Malay pirates. They are represented as being able to defend their position, through good discipline, until help arrived. At his court martial, Captain Maxwell of the Alceste addressed the court. His address was reported in terms that are ideologically driven: 'from the captain to the smallest boy, ail were animated by the spirit of Britons; and, whatever the cause was, I ought not to regret having been placed in a position to witness all the noble traits of character this extraordinary occasion called forth'. The author of the account compares this behaviour with 'the want of order and prompt obedience' that characterised the French crew of the Medusa .

When a British warship foundered, it could be taken for granted that the circumstances of the tragedy reflected on the nation. But the relationship between national interest and the success of merchant shipping was perhaps more open to question. Adam Smith, for example, argued that the interests of merchants did not always coincide with those of the public. In this context, we find counter-emphasis placed on the national significance of merchant voyages. The account of the wreck of the Halsewell East Indiaman, lost in 1786, explains that the objects of the voyage were 'highly laudable, to extend the commerce, and to promote the revenue, of the state'; and continues that in such cases: 'not only the state itself but every member of the common-wealth is unquestionably interested'. In a period when the government was taking greater control of the East India Company, the Halsewell account blurs the distinction between private and public interest. The ship carried 'pleasing hopes [...] which are the main springs of industry, the foundations of commercial spirit, and the conductors to private wealth and honour, and public advantage and aggrandizement. Essentially, the voyage was an imperial venture; on board were well-connected individuals about to embark on careers that would further British interest. More than lives and goods were lost when the ship went down.

Perhaps for this reason, narrators of disasters involving merchant ships are at pains to point out that though merchant seamen may panic in a crisis, the behaviour of their officers and of any regular armed forces on board is exemplary. When the Halsewell was wrecked:

The seamen, many of whom had been remarkably inattentive and remiss in their duty during great part of the storm, and had actually skulked in their hammocks, and left the exertions of the pump, and the other labours attending their situation, to the officers of the ship, and the soldiers; (who had been uncommonly active and assiduous during the whole of the tremendous conflict,) rouzed by the destructive blow to a sense of their danger, now poured upon the deck, to which no endeavours of their officers could keep them whilst their assistance might have been useful.

Similarly, in the case of the loss of the Kent East Indiaman, the soldiers on board reportedly behaved much better, perhaps because of their training, than the majority of the seamen. They ensured an orderly evacuation into the ship's boats, women and children going first, and stayed with their officers long after most of the crew had escape.

III

Many shipwreck accounts describe the adventures of survivors including captivities in foreign lands. These stories, set in the 'contact zone’ where Europeans gained first-hand experience of different ways of life, reveal aspects of contemporary nationalism and changing perceptions of cultural difference. Popular survival literature was part of the growth of a mass print culture and survivors returning from shipwreck or captivity often published cheap editions of their adventures for this market in the hope of financing a fresh start. Descriptions of captivity among other peoples added greatly to the interest of shipwreck narratives, partly owing to a vernacular tradition in anthropology concerned with defining racial characteristics (or stereotypes), and partly because they offered additional themes of sex and slavery. Travellers and seamen had long been urged to collect geographical and economic information that might be of use to Britain. Now the public was becoming increasingly aware of different peoples and liked comparative accounts of different lifestyles. George Keate, author of A narrative of the shipwreck of the Antelope which was wrecked on the Pelew Islands in 1783, is aware that this will add interest to his own account:

I therefore feel some satisfaction in being the instrument of introducing to the world a new people; and a far greater one, in having the means in my power, of vindicating their injured characters from the imputation of those savage manners which ignorance alone had ascribed to them; for I am confident that every Reader, when he has gone through the present account of them with attention, will be thoroughly convinced, that these unknown natives of PELEW, so far from disgracing, live an ornament to human nature.

Some travellers who had been harshly treated in their own country professed to find non-European peoples more 'civilised'. Drake Morris, a London merchant whose faith in 'British liberty' was much reduced after being pressed for the Navy, later advised his companions in misery to give themselves up to the inhabitants of the island they found themselves on. 'I have been amongst many barbarous nations, and I have never found the worst of them so cruel as my own countrymen'. He added:

The people of foreign nations were not so cruel as they might have heard, and that, as to savages that eat men there were no such in the world; nor do I, in my conscience, believe there are. The Indians are a people that love honest dealing; and, in some places, where the white people have stolen them away for slaves, or otherwise ill-treated them, they may have looked upon them as enemies, and treat them so at sight; but otherwise they were a friendly and well-meaning people.

Still other peoples were represented as 'noble savages' or occasionally demonstrated behaviour deemed worthy of Western nations. In the 1790s, Captain Campbell, a former cavalry commander, met with bad weather on a voyage from Goa to Madras. The ship seemed to be on the point of capsizing but 'on the instant, a Lascar, with the presence of mind worthy of an old English mariner, took an axe, ran forward, and cut the cable' (so that the mast was jettisoned and the ship righted. Travellers appreciated that the behaviour of other peoples could be used as a means of criticising corruption in British cities. Once ship wrecked, Campbell becomes the captive of a tierce native ruler intent on driving the British from India. A Lascar who survived the wreck pities Campbell, cast ashore naked. He takes the cloth from round his waist, tears it into two and gives Campbell half. The moral is underlined:

This simple act of a poor, uninformed black man, whom Christian charity would call an idolater, Capt. Campbell considers as having more of the true and essential spirit of charity in it, than half the ostentatious, parading newspaper public charities of London.

Other accounts refute seemingly idealistic views of native peoples. Pierre de Brisson, whose 1789 account of shipwreck and ill-treatment by nomadic tribes between Senegal and Morocco was reprinted many times, writes:

These wandering tribes, which, while it presents us with a melancholy picture of the depravity of human nature in a state of rudeness may serve to convince pretended philosophers, who are fond of bestowing encomiums on savage life, of the ridiculous absurdity of their opinions.

De Brisson typically judges others by Western European standards, as when he implicitly compares Arab practices with those expected of European merchants: Perfidy and treachery are also two vices înherent in every Arab. and on this account they never go out of their tents without beîng armed. They could never carry on business by granting written securities; for he who received a bond would assuredly be stabbed by the person who signed it: they always carry whatever they have most valuable in a small leathern purse, suspended from their necks.

Such anecdotes are part of the process of 'fixing' relations between Europe and other continents. In general, shipwreck narratives portray stereotypes: Turks and Arabs are labelled despotic, treacherous and cruel races. Travellers dreaded being wrecked on the North African coast, though admittedly, in the eighteenth century, European governments still found it necessary to maintain a system for ransoming enslaved captives from the Arabs in North Africa. Malays were 'extremely vindictive, treacherous and ferocious; implacable in their revenge'. When reduced to desperation by gambling debts or opium dependency, they were given to 'that singular and barbarous custom of running a muck' when they drew a creese (dagger) and destroyed all they met until destroyed themselves.

The popularity of shipwreck narratives may have helped establish racial stereotypes. Survivors from the Grosvenor in 1782 and the Hercules in 1796 were menaced by the inhabitants of Caffraria in North Africa. The Hercules account depicts some Caffre tribesmen as hellish savages:

He presented a picture truly infernal. He wore a leopard's skin; his black visage was bedaubed with red ochre his eyes inflamed with rage, seeming starting from their sockets, his mouth wide opened, and his teeth gnashing with exasperation.

Yet the same account asserts that although the Tambouchis tribe were reputed tobe 'the most ferocious, vindictive, and detestable class of beings' in Caffraria, 'the purpose of this atrocious calumny, is to screen the enormities perpetuated by the Dutch colonists.

Recent post-colonial theory has suggested a connection between the representation of racial types and the desire to justify conquest. A reading of shipwreck narratives provides some support for this view. Generally, European writers praise indigenous peoples for their humanity only when they offer no threat to European dominion, or their territory offers no opportunity for colonial exploitation. Native rulers capable of offering resistance are scorned for their alleged tyranny and irrational cruelty; peoples in areas considered ripe for colonisation are represented as savages in need of a rational civilising influence. For example, De Brisson's critical account should be read in the context of French imperial ambitions in Africa. The French had maintained trading interests in Senegal since the 1650s. Little of permanence was achieved in the eighteenth century, partly due to the resistance of local peoples, though West Africa and Algeria later became colonies. As we might now expect, even later accounts which strive to be more discriminating describe the characteristics of different races in essentialist terms, categorising them neatly in the hierarchical language of the West as 'other' and inferior.

Shipwrecks and tales of survival also allow writers to represent the margins of Western culture and to identify the knowledge and values that underpin it. As a metaphor, shipwreck and survival on remote shores operated so strongly that some writers used it as an expression of profound emotional and mental dislocation. John Newton, slave trader and later evangelical preacher, described in his An authentic narrative ( 1782) how he was put to work by a slave trader with only one mathematical book to keep him sane:

Though destitute of food and clothing, depressed to a degree beyond common wretchedness, I could sometimes collect my mind to mathematical studies [...] I used to take [Euclid] to remote corners of the island by the sea-side, and draw my diagrams with a long stick upon the sand. Thus I often beguiled my sorrows and almost forgot my feeling - and thus, without any other assistance, I made myself in good measure, master of the first six books of Euclid

In Newton's Narrative the guilty ex-slaver seems to be claiming for himself the pity normally elicited for victims of storms at sea. At the same time, his reading of Euclid seems to reaffirm the superiority of Western civilisation, perhaps allowing him a measure of self-justification.

Shipwreck might mean instant death or a protracted ordeal. Shipwreck narratives such as that of the Medusa encouraged readers to consider, however briefly, the social and moral imperatives that ought to govern the behaviour of people driven to ding to existence in desperate conditions. Often their actions seemed to define the limits of humanity. There was no shortage of examples nearer to home. The loss of the Earl of Abergavenny, captained by William Wordsworth's younger brother John, led to 'shocking scenes in the shrouds' as people clambered above the water when the vessel grounded.

Before the notoriety of the Kent disaster in 1825, it is by no means certain that 'women and children' first was accepted as a laudable convention. When the Centaur went down, Captain Inglefield jumped into a pinnace and left the majority of his crew to their fate. Inglefield's account, written as soon as he reached safety then published on his return to England in 1783, relates his 'painful struggle' - whether to leave with the pinnace, or stay on the ship and perish. Love of life prevailed. Inglefield called the master, the only other officer on deck, to accompany him (presumably ordinary seamen were not eligible) and jumped overboard. At his court martial he was acquitted with honour.

TO BE FOLLOWED